Welcome to the latest edition of Climate Focus.

Thank you to the new subscribers since the last edition earlier this week. I hope you like what you are reading.

And a special acknowledgement to the wonderful people who very thoughtfully wrote back with kindness and warmth. You know who you are, and you have my gratitude!

Living In A Greenhouse is a labour of love and I’d want it to be something that you will want to read. Please feel free to write to me with your thoughts and comments, and anything you’d like to see more of =)

Right. On to this week’s business.

Negotiations are going well into the last day of the fortnight-long summit. We have had a few major breakthroughs with 100+ countries agreeing to methane cuts, nearly 90% of global emissions are under net-zero pledges, and a global warming trajectory that’s improving with each commitment.

However, there are a few key issues outstanding that are essential to operationalise these promising developments. I am personally interested in seeing positive outcomes on ending fossil fuel subsidies, additional binding climate finance commitments, and a global carbon market.

I write about a couple of them in this edition, as more details emerge. But first, two frenemies hug it out.

Let’s dive in.

Climate Science? Nah, it’s Theatre.

China and the US together accounted for 43% of global emissions in 2019.

The two biggest emitters made nice with each other and issued a joint statement after a few days of petulant bickering, but no additional enhancements to previous pledges were announced.

Doing it together is classic political showmanship, and (unfortunately) one that is warranted given the dire state of mistrust between the developed and the developing world over coordinated global climate action.

John Kerry, (yes, the same man with the very cool title), relied on history to drive home the significance of the joint address, likening it to the nuclear arms pact struck between Reagan and Gorbachev in the 1980s (yes, I am rolling my eyes too).

The Chinese Climate Enovy, Xie Zhenhua, was not to be left far behind. He said:

In the area of climate change, there is more agreement between China and the US than there is disagreement.

(I don’t know what that means. Do you?)

The 16-point joint statement does not contain any specific additions to existing climate commitments by both countries, but offers clarity to previous interpretations of China’s perceived lack of urgency on climate action within this decade. In my opinion, that is a really big win. (‘2020s’ features 7 times! Cmd+F ftw).

Here are other notable highlights -

Both countries agreed to establish a “Working Group on Enhancing Climate Action in the 2020s” and that they intend to “will meet regularly to address the climate crisis and advance the multilateral process, focusing on enhancing concrete actions in this decade”

China additionally agreed to a key clause that it previously objected to in the COP draft to urge countries to update their emissions targets by 2022. (!)

Methane heavily featured. Despite the emphasis on cutting Methane emissions, China decided to pursue national action to achieve its targets, alongside collaborating with international efforts to enhance methane emission control and mitigation. Any reference to joining the US-EU led global methane pledge was noticeably absent.

Death By (COP) Drafts.

There is not a lot to read into a preliminary draft floated by the COP26 Presidency. I will just say one thing though.

Fossil fuels has finally found its place in an international climate document.

Calls upon Parties to accelerate the phasing out of coal and subsidies for fossil fuels;

Never in the previous 25 editions have we managed to achieve this.

It is evident that burning fossil fuels is the single biggest reason for our current climate reality, and to not acknowledge that just seems farcical.

I am waiting with bated breath to see if it will be included in the final draft that is expected to be released after the conference ends later today. The sentiment suggests otherwise.

(Update as of the time published: Fossil Fuels and Coal Phaseout remain (so far)!)

Fool me twice, still shame on you.

The Kyoto Protocol signed in 1997 introduced the world to the world of ‘carbon credits’ and assigned units that countries can emit.

Emissions trading, as set out in […] the Kyoto Protocol, allows countries that have emission units to spare - emissions permitted to them but not "used" - to sell this excess capacity to countries that are over their targets.

It was a catastrophic failure and I am putting it mildly. However, Kyoto Protocol was the first multilateral climate agreement, and there wasn’t a lot that the countries agreed on. Reparations were attempted during the Paris Climate Summit of 2015 on a global market for these credits, which gave birth to the fiercely contested ‘Article 6’.

The point of contention is specifically about how to trade emissions internationally, and at the same time ensure everybody wins.

There’s only one way that could have gone and it went that very way.

Here is how the problem is playing out. A country plants a forest-sink and another high-emissions country buys ‘carbon credits’ from forest-land to offset its pollution. Can the country with the forest count it within its emissions targets?

Countries are locked in negotiations over figuring out a rule-book to avoid this double-counting.

Under the plan being put forward, one class of units could be traded by countries and used to meet their emissions reduction targets. Only one country would be allowed to claim credit for the emissions cut. The second class of units would not be permitted to be used by countries to meet these targets but could be sold to other buyers, such as companies.

Negotiations are expected to go well into the last day with early indications that a deal isn’t as straightforward as previously thought. Brazil is home to the world’s largest carbon sink and any deal of a global scale will need a sign-off from the South American nation.

Brazil was one the top countries for emissions-reduction projects under the defunct Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), and has in the past argued that all those credits should be allowed to make up for pollution cuts after 2020.

There were high hopes this time, especially with Brazil softening its stance since the failed-Madrid negotiations in 2019 over counting of credits.

With or without a successful outcome to the negotiations, there will still be a functioning global carbon market.

But with clear rules on accounting of carbon credits and tiers to country and company offsets, the general air of mistrust over the integrity of these markets might just be lifted.

Bonus

Another day. Another alliance.

‘Six-ish’ countries came together to sign on to the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance. Formed by Denmark and Costa Rica in September, its latest signatories include France, Greenland, Ireland, Sweden, Wales and the Canadian province Quebec.

The alliance hopes to mount pressure on countries to stop fossil fuel expansion. However, it only focuses on upstream oil & gas, i.e., exploration and production and does not include oil refining, petrochemicals and other by-products.

Committing to fully curb new oil and gas exploration is not popular among most countries, with a ‘continued, but dwindling reliance’ on fossil fuels seeming to be the preferred articulation.

Interestingly, none of the BOGA members are major oil producers but it does pave the way for other countries to make such commitments.

Another Day. Another Pledge.

<Scroll back to previous GIF. Please and thank you>

At least six major automakers and more than two dozen national governments pledged on Wednesday to work toward phasing out sales of new gasoline and diesel-powered vehicles by 2040 worldwide and by 2035 in ‘leading markets’.

It’s a significant win in the current COP Presidency’s agenda to get countries to move away from combustion engines and towards electric vehicles.

The automakers who signed the pledge included Daimler, Ford, Mercedes-Benz, General Motors, China’s BYD and Volvo. Together, they account for roughly one-quarter of global sales in 2019. The world’s largest car leasing company LeasePlan joined the deal, while Uber also signed, committing to make its entire fleet zero emission by 2030.

Noticeably, four of the five largest auto manufacturers - Volkswagen, Toyota, the Renault-Nissan alliance, and Hyundai-Kia, did not sign on to the pledge.

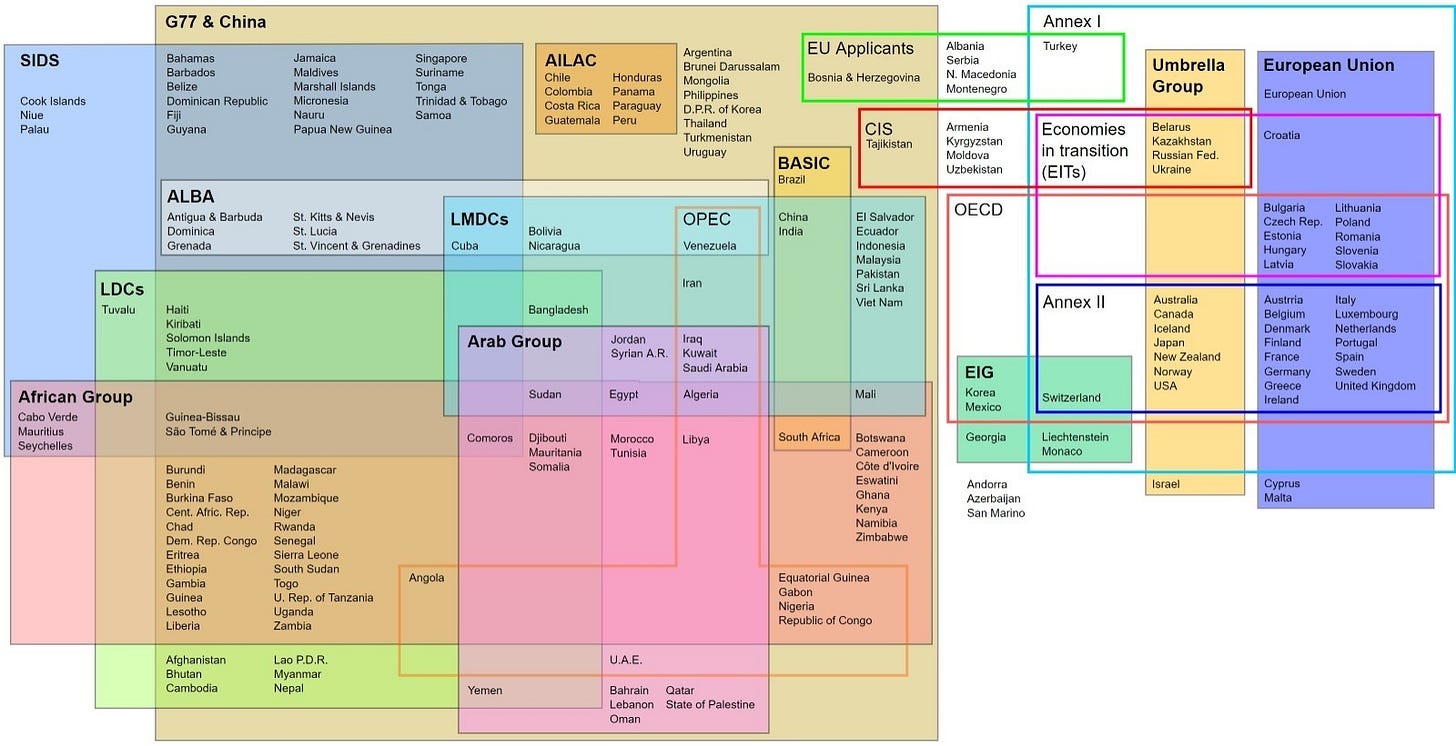

Who are these negotiators you ask?

Bends your mind, doesn’t it?

Banter

When you can’t help but laugh